Llyn Foulkes, The Awakening, 1994-2012.

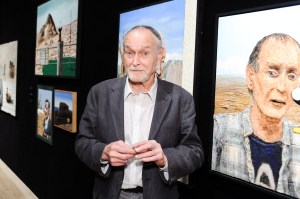

Llyn Foulkes is an L.A.-based painter who has built up an oeuvre of landscapes, portraits, mixed media works and large-scale tableaux over a 50-year career. He is also a celebrated musician known for his self-built “Machine” in which he plays an amalgamation of instruments as a one-man band. In honor of his career retrospective at the New Museum, Foulkes talks to TIME about his motivations, materials and the state of the American Dream.

When did you first realize that you wanted to become an artist?

Probably at the age of 5. When I was a kid I drew cartoons. I also got into music, and then I saw a book on Salvador Dali and that inspired me to be a painter.

Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s much of your work seemed to focus on the fantasy of the American Dream. Is this something that still preoccupies you?

The American Dream has kind of gone to pot now. Commercialism has just [gotten] absolutely crazy. The American Dream now just seems to be about money and fame.

You’re a known critic of conceptual art. What do you think the fault of conceptual art is?

I think a lot of conceptual art has so much to do with an idea rather than a process. I’m a big believer in the process because I think that’s how you discover things. I think conceptual art has been totally overblown. They’ve been following Duchamp now for almost a hundred years—in 2014 it will be a hundred years. And they keep acting like he’s new.

Recently you’ve worked on several three dimensional tableaux, such as The Lost Frontier. How did you decide to work in a larger format?

The constructions which you’re referring to— it was because I started getting deeper into the painting and using assemblage and painting to create very deep space. The Lost Frontier is probably the deepest painting that I ever did. It feels like you could walk right into it, and that’s what I’ve been after for the past 20 years.

Are you disillusioned with the state of the art world today?

I think because so much is happening on the Internet now, it’s a pretty jumbled mess. I think so many young people see images so quickly and so fast that they don’t really get into the core of picture making. Personally, I like paint, I like the hand, I like the process. I just think it’s too easy—I think everyone thinks they’re an artist now.

Can you explain what “The Machine” is and how you came up with it?

I started collecting horns and bells when I was 10 years old. And then I got into jazz and I played the drums. I stopped the music when I did my first paintings at the age of 18. Then I started again in the ‘60s, and I was in a rock band from ’65 to ’71, and then realized that music was getting too loud. It became how loud it was rather than how good it was. So I went back to my roots and I started a band called The Rubber Band. We were on the Tonight Show, and then in about 1979 I started building my Machine. It’s a one-man band and I’ve been doing it since 1980.

Why do you prefer being in a one-man band as opposed to playing with others?

I like playing with others, but I have full control as a one man band. I can stop whenever I want. I write all the music, I play everything myself. I don’t have to worry about losing musicians, having to replace people. It’s part of my core now.

How do you hope that viewers interact with your art?

People are going to react in different ways. I just want to be visible enough that people can see what I do. Art is so controlled now by money and the stock market; it’s very hard for a lot of artists to be seen.