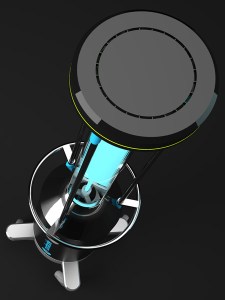

M2 Landscape for Quinze + Milan, 2004.

Kenny Kim

Scott Wilson knew he had an artistic bent as a young child, but it wasn’t until he founded the Chicago-based MNML that he was able to marry a passion for design with his entrepreneurial vision for a 21st-century hybrid design studio that embraces both corporate brand-building and disruptive startups. This October, he is recognized as the recipient of the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Award for Product Design (2012). Wilson has worked on wide-ranging projects that range from LunaTik watches for the iPod Nano and Microsoft XBOX 360+ Kinect to baby furniture and medical technology, which he recently spoke to TIME about.

When did you first realize that you wanted to be a designer?

I was always drawing, growing up, and I was always the artist in the class. I also liked math and physics and how things worked, so in high school my guidance counselor told me to be an engineer. My art teacher was actually pushing me to be an illustrator or graphic designer. Product design and development seemed to combine the two—technical, creativity—so it was a good fit. I was fortunate to find something, and to end up loving it. Twenty years later, I still can’t turn it off.

(MORE: Go Behind the Scenes on an Open House Weekend)

MNML

Your design studio is named MNML. Would you say that’s also an accurate description of your design aesthetic?

I think it’s appropriately minimal. Not everything has to be absolute minimalism; it’s just taking out what is not necessary. But you can’t prescribe minimalism for every client. We try to take what we do and our flavor and mix that with the DNA of the brand that we’re working with. It comes down to the consumer and the market you’re designing for. But you can always do it more minimally than what’s existing out there in the market.

MNML

You used Kickstarter in 2010 to fund the TIKTOK + LunaTik project, which turned the iPod Nano into a multifunctional watch. How did you decide to fund it that way?

I had this idea for a watch, and I was just pitching it to other brands. They all thought it was too expensive or they were going to do their own. So I had this thing that I’d designed on the side, and I figured it was either going to die in my notebook or on the shelf as a prototype, or I could try this thing Kickstarter. I pretty much did the video myself on a Sunday and threw it up there. I had no idea it would go like crazy. I figured other people that were watch fanatics and some Apple fanboys would buy it, but there’s a lot more out there than you realize. And it went across generations.

You seem to have an affinity for watches and watch design. What about them appeals to you?

It’s funny—before I went to work at Nike to do their watches, I think I had one watch. And I probably never wore it. Working at that scale, of fractions and millimeters, and designing from the inside out—they’re like little machines. You’ve got limited real estate and a lot of constraints. It’s got to be comfortable; there’s an ergonomic, wearable aspect to it. Any product that you ask people to put on their body is inherently harder than designing an Xbox that sits on the table.

(MORE: Why Secret Frank Lloyd Wright House Should Not Be Torn Down)

MNML

You’ve also designed a number of medical products recently. How did those collaborations come about?

Our first medical client was SonoSite. They do point-of-care ultrasound, so we helped them with a new system that just launched [SonoSite EDGE Ultrasound System] and another system that’s launching in January. Shortly after that, a woman walked in the door who had this breakthrough technology, an algorithm for identifying turbulence in your arteries. Her husband had died at a young age from this, and she was a Stanford engineer and figured out a way to identify if you have any kind of blockage in your artery. My mom had passed away at 51 from a sudden cardiac event, and my daughter had just been diagnosed with ASD [atrial septal defect] which is a hole in the heart that didn’t close—it’s fine now, a year or two years later—but it was on my mind. So we worked with her on that [a non-invasive testing system], and actually she’s in trials right now. And then Surfacide [a hard surface disinfection solution] started with a guy who’d been working on infectious diseases in water treatment for years, and a lot of his corporate clients were saying they needed something for their patient rooms. We ended up working with him on figuring out a new UV-C light system that can kill these “superbugs” at a cellular level, versus right now, where state of the art disinfection is basically using bleach. I get more excited about that stuff, which isn’t that glamorous, compared to the next iPhone case or watch or whatever.

It’s in a realm that helps people in a different way.

There’s a lot more opportunity in that space. Everybody wants to do the iPhone cover, and it’s like, really? They have so many people working on that. They don’t need more.

Is there an area of modern life that you feel is underdesigned?

The personal health dashboard is a big one, and people are focused on it. Bikes and cabs—the infrastructure for transportation that supports alternatives to cars is a bit broken, and a tough problem to solve. I’ve always had a problem with water bottles. We consume so many water bottles, and more and more companies are starting to take on the problem, but it seems we just keep consuming disposable water bottles.

How much of design for you is function, and how much is form? Do you find it hard to satisfy them both in some projects?

It’s almost all function. The form part is easy once you’ve defined the problem and designed the solution. If you have good research or good insights, the thing kind of designs itself. Putting a form around it is the easy part, really. Finding the insights and finding the connections and the right puzzle piece that may be missing, that’s the hard part.

MORE: Q&A: Ford Chief Creative Officer J Mays on the Redesigned Fusion